Once was a Smart State: Intellectual Leaders in Queensland

1859-1989

A Typology of Thinkers and their Interrelation in Queensland History

Criteria and Methodology

In the research proposal an idea of a roadmap for public history was presented: a social history of thought in Queensland through modelling the place and role of key thinkers in relation to the Queensland society. The project is looking, not merely as a society of politicians, churchmen or women, or writers (and so forth), but across a broad intellectual landscape.

The key question is how a thinker brings a host of ideas from political, religious, and literary worlds, to form a model position or an outlook within the broader society, and how those thinkers groups themselves together (or not). The last part of this question leads, for the project, other questions:

- How are these model positions or outlooks within the broader society represented?

- How much cross-boundary development of thinking was occurring between political theorists, philosophers, literati, and other scholarly thinkers?

- In terms of world history, where are the intellectual sources coming from, and how are the contents of these sources contextualised in Queensland history (particular time period and place)?

Here, in this document, I consider the criteria and methodology for the project, which flows from the research questions above.

The obvious criterion is one that is inherited from the understanding of world history. We know who and what to look for because the intellectual themes are so well established. The ideologies arrive on different planes of thought:

- on one divide Christian, Agnostic or Atheistic, Catholic and Protestant, and perhaps Indigenous and "Oriental" (the term being deliberately critical as in Said's work);

- on another divide, Conservative, Liberal, Socialist; and yet another divide, Agrarian or Pastoral, Industrial Labour, and Capital; and

- yet again another divide, Romantic, Rationalists, and Scientific or Empirical.

The paradigms here do not exclude others. Other important social-intellectual divisions identified will be added. There will also be both overlap and discontinuity. However, we now have the first methodological step and criterion. The first task is to list a certain type of thinker, and one that had a particular place in Queensland society (Step/Criterion One). There is both a process of exclusion and a process of prioritising.

Step/Criterion Two: Time Frame

The focus for the project is 20th century thinkers. However, a few nineteenth century thinkers will be included on the basis of the impact of their ideas for Queensland society in the 20th century. The starting point is the foundation of Queensland statehood in 1859. At the other end we have a finishing point, for the purpose of having the historical distance to be able to fairly judge the application of criterion one, as well as other criteria. The year 1989 is assigned as a rough cut-off point for the project. The cut-off is somewhat arbitrary but it does have logic due to the impact caused in Queensland society from the conjunction of the end of the Bjelke-Petersen Government and the return of Labor Government in Queensland after three decades. Although this excludes contemporary thinkers, it is anticipated that a second project to look at more recent history can ride on the success of this project, at a later date.

Step/Criterion Three: Place

Obviously the place we are looking at is the state of Queensland, but that tells us little of what is a fair relationship between the thinker and the place of Queensland. There are famous thinkers who were born in Queensland but had little connection to the place. The world-famous palaeoanthropologist, Raymond Dart, was born in Brisbane in 1893, but his work had no apparent connection to Queensland society. Equally, there are notable thinkers who retired to Queensland or simply happened to die in Queensland. The critical question relates in the next criterion (Four). What must be considered for inclusion, and obversely, exclusion? For a thinker with a connection to Queensland to be listed it will be their impact that ensures inclusion. This will be explained further below, but a different point about place follows. A thinker, to have impact on Queensland society, does not necessarily have to have a physical connection to the place. Furthermore, the connection between the thinker and Queensland can be very brief, and yet their ideas have had a profound influence on Queensland society. Fortunately, we don’t have just the option to include or exclude for the project.

A project of this nature needs to consider a sense of priority in the listing of thinkers. We can first look to adding in the list those thinkers whose work primarily operated within the state boundaries. Secondly, we can also add ‘outside’ thinkers who were visitors. What we are aiming for is an understanding of social-intellectual transmission within Queensland. Ideally, our focus is thinkers whose primary work in Queensland was that social-intellectual transmission. However, we must also consider the accidental or ad hoc connections here. This includes thinkers who only briefly pass through Queensland but left an intellectual legacy in some quarter of the broader society. There were also world famous thinkers to consider who never ventured to Queensland, but whose direct correspondence left a mark. All these different categories can be included but the priority in the project goes from finding those thinkers who are closely connected to the place to noting those who had only fleeting connection but whose brief encounter brought significant impact.

Step/Criterion Four: Type of Impact

In each case considered in a list of thinkers, the most important criterion is that the type of impact in the Queensland society is 'social-intellectual'. We have congregation around a clearly definable set of ideas. The thinkers don't isolate themselves in thinking about a model position or an outlook. Each is part of an important interest group as part of the broader society, and each is also engaging with members of the society outside their particular grouping.

There are two methodological points here. First, we do have to exclude, unfortunately, brilliant thinkers connected to Queensland whose contributions lack the impact we are trying to map. There are thinkers whose work has delivered major technical insight. It can be argued that there are cases where technological development has brought major social-intellectual impact, sometimes more profound than any ideology. While that may be true, the aim of the project is not simply to map the thinking of the key thinker, but mapping the thinking within Queensland society (as a social extension of the individual thinker). Most technological development profoundly re-shapes the society without changing the patterns of thought in the broader society. In fact, and very unfortunately, the technological agenda can often have a debilitating effect for social-intellectual engagement. As a caveat, though, it is possible to include a thinker whose work is technological development if it can be shown that she or he also made a significant contribution to such wider evaluation.

The second point is the complex relationships which are ultimately mapped. As noted above, intellectual divisions will both overlap and be discontinuous. Hence, thinkers will bring conflict within their particular grouping, and alliances will emerge across groups which otherwise appear much disassociated.

In this regard the project will endeavour to be as inclusive as possible. It will cover the whole socio-political spectrum, considering both forces to conserve and overthrow ideas or beliefs. Nevertheless, there is one exclusionary factor in this part of the process. There are so noted “thinkers” in Queensland who do have a role in social-intellectual transmission, but on closer examination their role is one of promulgation of ideas without any substantive understanding. One naturally tends to think of politicians, and often a populist type of politician. Their rhetoric is of crowd or voter control and what they present has very little explanatory value. This is a challenging methodological step of exclusion in the process.

Although ideologies, and populism is a good example, can be just a matter of power-play for individuals, or parties of individuals, there does exist connected sets of ideas which are meant (and is) to be taken as true belief, rationally-held. A ‘populist thinker’ is not a contradiction in terms. Even the most cynical of politicians will self-justify their ambition on a set of ideas. At these ends of socio-political spectrum (and there are clearly both Left and Right versions), it is challenging to tease out what is pure nonsense from what are very weak socio-intellectual frameworks, in regards to reason (logic) and evidence. But it is not an impossible task to do so, and it is important, for the sake of understanding ourselves, to map the illogical formulations and misconceptions which have been transmitted throughout the society (and thus it is not a question of arguing the point with the fanatic). Furthermore, whether populist or not, the list will need to include thinkers who are not particularly scholarly in their disposition. They are thinkers who have played the role, in part, of the social or political theorist. This role might not be self-consciously undertaken, as community or political leaders; however, in their considerations these thinkers have not merely unreflectively promulgated ideas. The thinkers are included in the list because they have, even in a minimal sense, engaged with the ideas in understanding.

Mapping and Modelling

This project might be seen as a work of historical sociology. That assessment is only partially correct. The project, though, is a collaboration of Queensland social historians whose primary analytical tools are historiographical. A few significant methodological points about the outcomes that the project seeks to achieve should be explained. First, while the project does aim at producing a few models that show the interrelations between the thinkers and the society, it does not take such models as conclusive. What is important for the historian is not so much the structure of the models but how the model can deliver a way to both interpret and produce a narrative of the past. Whereas the sociologist is concerned with a pattern which she sees emerging from the historical data, the historian is concerned to use the pattern to tell the story.

There is double role here for the historian. The historian is the one who gathers and filters the data for the sociological assessments. Once the models are produced, the historian acts as a verifier in the process of fleshing out the relational lines and hubs as researched narrative. If the story cannot fit particular parts of the model, on the basis of the historical evidence, then it is a problem for the sociologist, not the historian. The model ought to fit the researched narrative, not the other way round. While it is true that the model affects the historical research method, there is an empiricist bias in viewing the model as the abstract entity, and after continuous verification in research observation, if there is a problem in the fit, it is the model that needs to be revised.

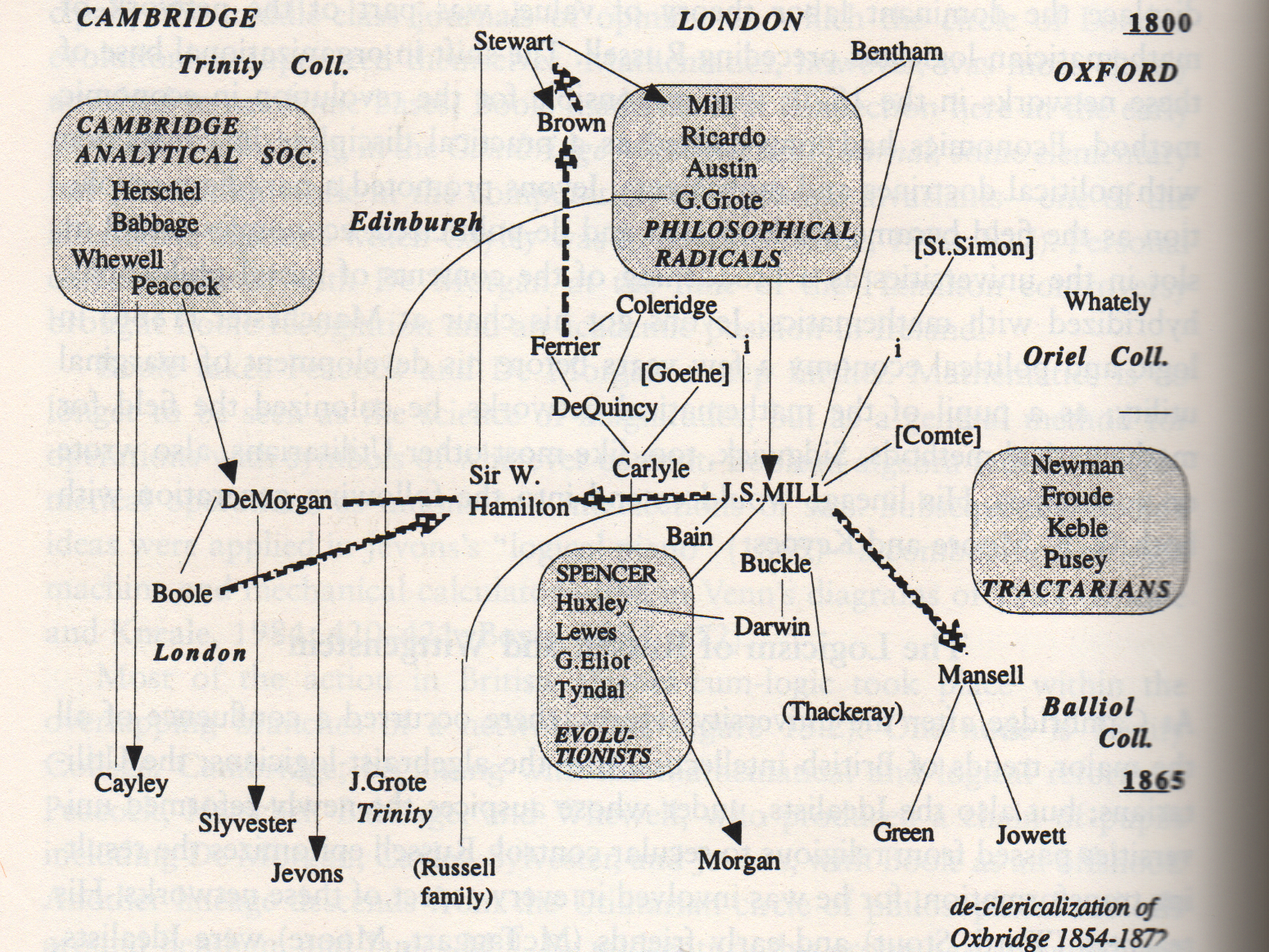

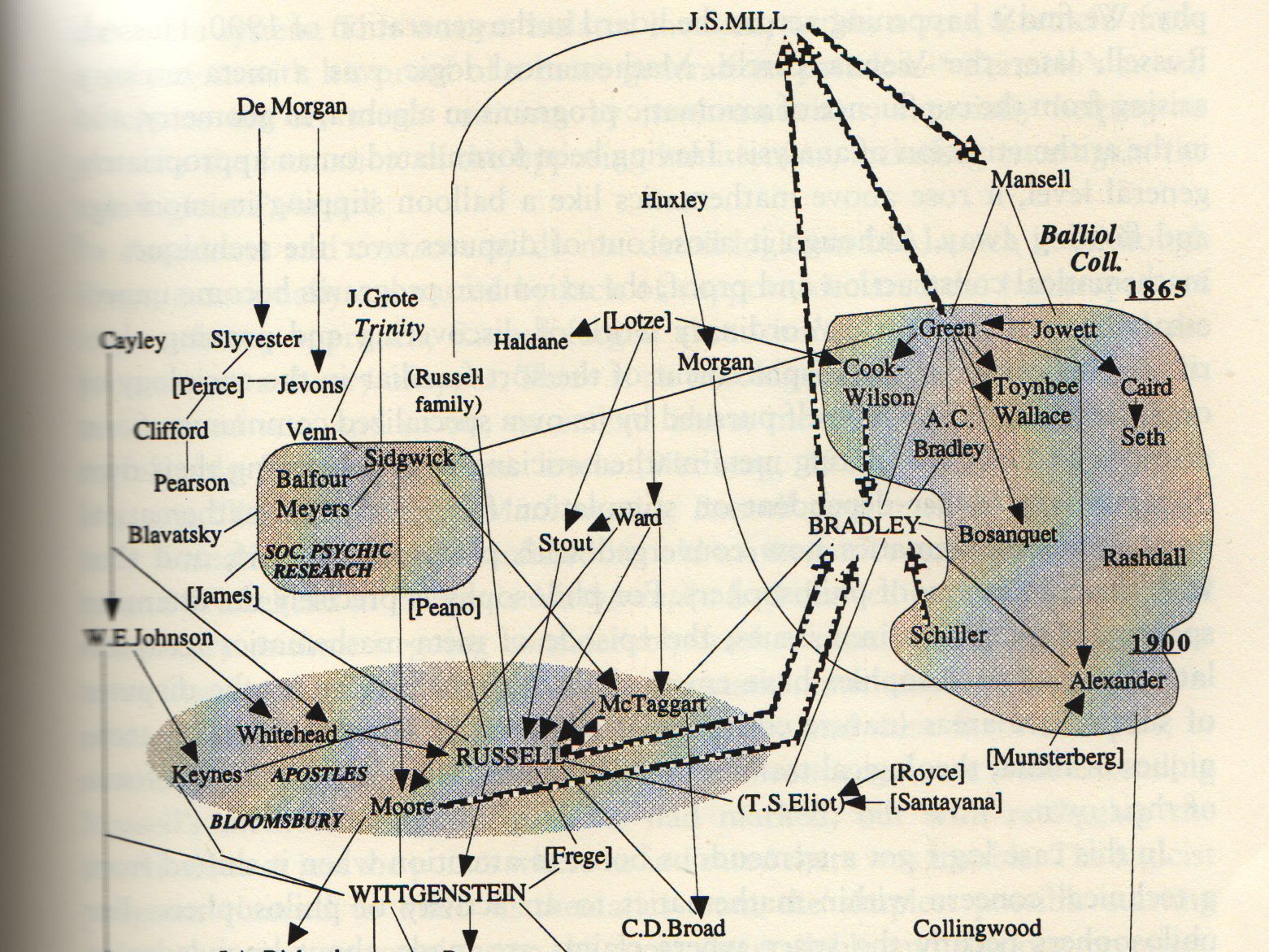

Secondly, the inspiration for this work, in combining historical sociology and social history, comes from what Randall Collins calls, “The Sociology of Philosophies.”[1] An important point is that this approach is not sociology of knowledge, and least of all, “the Strong Programme” in the Sociology of Knowledge. We are not dealing with an epistemological thesis for knowledge-construction. We can offer Robert Nozick’s tracking theory as a possible description of what is occurring in our own knowledge-construction for the project, but beyond that the traditional view of knowledge having transcultural and trans-historical qualities is merely accepted; for the sake of keeping the project manageable in the already large arenas of history and sociology.

It is important, however, to clarify that such a traditional epistemological stance does not infer an ethnocentric outlook for the project. There can still be significant disjunction in the historical methodology from past practices. Knowledge-construction has transcultural and trans-historical qualities, through the whole gambit of reason and observation (human capacities), but it not mean that its content does not have relative cultural and historical conditions. Disagreements about reason and observation can occur both between and within cultural groupings, while at the same time a project like this can be inclusive of all thinkers, according to the transcultural and trans-historical criteria. Certainly, there is a challenge. Past practice of excluding women and minority groupings from the historical records, has meant Anglo-Celtic (white) males dominate the literature. As much as possible, the project will endeavour to be inclusive of thinkers as representative of those groupings which have been left out of previous investigations. If the project is still weight more to Anglo-Celtic (white) males, it won’t be due to a lack of effort to correct the record towards greater comprehensiveness.

Collins’ sociology of philosophies approach is fairly modest in its epistemic claim, which is that knowledge construction for what we see are the big ideas, broadly speaking, philosophies, come as “the networks of specialized intellectuals turned inward upon their own arguments.”[2] In putting forward his thesis, Collins views his stance as “not a self-undermining skepticism or relativism; that it has definite historical contours, as well as a general theory of intellectual networks…”[3] This project is not concerned to defend Collins’ general theory, which would not work, anyway, in the smaller time scale of Queensland history; and indeed, on the periphery of global networks. What it seeks to take from the sociology of philosophies is the outlook that, opposed to populist attack on elites, ideas come from groups of thinkers, and by mapping their relationship we can understand the social-intellectual development within the broader society. Collins’ argument is that there are focal points, nodes or communities of intellectual exchange, in the flow of attention and creativity.[4] Collins is concerned about the political interplay in the scholarship between debate and consensus.

The project has a different agenda. It wants to map the extension of the intellectual relationships from within the scholarly communities out into the broader Queensland society. In doing so, it seeks to meet, head-on, the pretentious Queensland populist outlook where various ideas across the spectrum are arrogantly appropriated without any acknowledgment of its historic source. Scholarship ought to be publicly engagement but there is no mistaking its necessary elitism. Originality in a coherent set of ideas takes years of training and engagement with the literature, and this is even truer if the ideas are to be sustained in good arguments. As much as the populist proclaims he does not need schools, universities, or anybody else to tell him what is what, such a stance is foolish nonsense. The populist is merely blind to the sources of his own ideology. Unfortunately, Queensland has had a history of that type of prejudice, “Don’t you worry about that!” Nevertheless, there are less known episodes in Queensland where intellectual communities did flourish and something of those endeavours resounded in the society. An understanding of that social-intellectual history, mapped and modelled, is what the project will deliver.

Neville Buch, MPHA (Qld)

Ph.D., Grad. Dip. Ed. UQ

Grad. Dip. Arts. (Philosophy), Melbourne

Neville Buch has a Ph.D. from the University of Queensland in the fields of Australian religious history and Queensland social history. Prior to his current consultancy work, he worked as the Research Officer for the Vice-Chancellor at the University of Melbourne, and at Griffith University. During these years, Dr Buch re-tooled himself with further formal studies in philosophy at Melbourne.

[1] Randall Collins. The Sociology of Philosophies. A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 1998.

[2] Ibid. p. 12.

[3] Ibid. p. 13.

[4] Ibid. pp. 14-15.